It’s 20 minutes until varsity soccer practice begins. I’m in my classroom watching Danny write a potential roster for the upcoming season on the whiteboard.

“Coach, do you really want to put four freshmen on varsity?”

“No. I don’t.” I check the clock. “But do we have a choice?”

Billy and I look over the list of names in silence.

“Coach?”

“Yeah Danny.”

“This is going to be a rough season.”

I look at him and smile. “I might be doing a lot of drinking this year.”

“Cool. I’m down with getting drunk.”

Danny is 22, one of my former players, and now my unpaid assistant coach. During his four years as a student, I’d never taught Danny, mainly because I taught Advanced Placement English classes. Danny would frequent my class, however, knowing that because the smart kids liked to read and talked quietly about what he called “English stuff,” the corners of my classroom made perfect crannies for him to curl up in and take a midday nap. Danny has since graduated. He’s a host at TGI Friday’s, the self-proclaimed “Dopest Host on the East Coast.” He’s a bit doughier than he was four years ago. He’s a good kid, dependable and always happy. But Danny is locked in that awkward stage of development, acting like an 18-year-old while trying to present himself as an adult.

I’m 34 and have the same problem. Maybe that’s why we get along so well.

As Danny continued to write and erase names on the whiteboard, my cellphone rang. It was my general practitioner, Dr. Thomas. The sight of his phone number made my skin jump and my stomach bottom out. Call it intuition or being in tune with the universe, but I knew bad news lurked on the other line. It’s funny how that works. How a “bad news phone call” seems to have a slightly distorted ring that gives you an electric, sinking sensation.

“Hello?”

“Jason, this is Dr. Thomas.”

“Hey. How are you?”

“We got your test results back.” His voice was flat, and his use of declarative sentences scared me.

“Jason, your blood tests came back fine. However, your MRI reveals something significant. Do you have a minute?”

“Significant?” Hearing the word – significant – made me think: “Oh,significant. That’s a good thing. It’s like saying, ‘My significant other makes the best burritos,’ or, ‘Sorry the bed is so lumpy, I stuffed a significant amount of money under the mattress.’ ”

“Jason, your images show significant cerebellar atrophy. Are you familiar with the term cerebellar atrophy?”

I thought, then spoke. “I know the cerebellum is part of the brain. I know atrophy means to shrink. Are you saying my cerebellum has shrunk, doctor?”

“Yes. Your images reveal significant thinning of your cerebellum, which occurs when brain cells die.” I somehow forgot significant can also have negative connotations.

“Die?”

Danny stared at me, then pointed to the list of names on the board. He proudly mouthed, “I got it!”

Dr. Thomas continued, “Jason, this is serious. Since this is the baseline image, we don’t know the rate at which the atrophy is occurring. The cerebellum controls muscle movement, balance, coordination, and eye movement. If you’re having complications in those areas, suffice to say your cerebellum has atrophied significantly.”

For a moment, neither of us said anything. His silence made me believe he had delivered bad news over the phone before. There was grace in his silence. He gave me a few breaths to digest the immediate facts of my life.

“Jason, I went ahead and scheduled an appointment for you with Dr. Paul Simon tomorrow at 10 am. He’s a local neurologist and a friend of mine who can answer your questions better than I can. I urge you to rearrange your plans to make that appointment.”

“Okay.”

After giving me Dr. Simon’s address, he said a few other things, but all I heard was, “Good luck and God bless.”

Dr. Thomas hung up. With the phone still against my ear, I looked over at Danny. He was laughing. He just wrote the word “poop” on the board. Danny loves the word poop. I’ve found poop printed on Post-it Notes on my desk and on my game-day lineup. Or etched into the Styrofoam of my Dunkin’ Donuts coffee cup. When Danny feels extra creative, he follows the word with a steaming illustration.

I wanted to call my wife.

I pulled the phone from my ear, punched up Cindy’s phone number, and stared at her name. I pictured her at home in the backyard watching the kids splash around in the kiddie pool. She’s wearing sunglasses and is stretched across a blue blanket with a glass of iced tea alongside her smooth brown thighs. She’s smiling with our young children, and they’re happy. Life, as they know it, is perfect.

I looked at Danny, forced a smile, and hung up the phone before Cindy could answer.

“Let’s go to practice, Danny.”

“Hey, Coach, check out the board.”

“Poop is right Danny.” Poop is right.

Practice ended, and I sat in my car. The keys were in my lap. I hesitated to call Cindy. To shift the car into drive toward home. Toward uncertainty. Life was going to be different now. I held a secret that was going to turn our life on its head. My tongue pressed hard against the diagnosis. It was powerful. Terrifying. And the longer I kept the secret, the longer life continued as planned.

But before I could leave the parking lot, I shared my secret with Cindy. I repeated the conversation I had with Dr. Thomas. Her voice quivered as she asked me to spell cerebellar atrophy. I knew she was taking notes. Dylan cried. He was six weeks old. I told Cindy I’d be home soon and hung up. I knew she was crying now. I was, too. Not a sobbing oh-Nicholas-Sparks-stop-pulling-at-my-heartstrings cry. Just hard chest chokes. Like the car was suddenly short on air.

I was scared.

I got home. Because we’re 21st-century beings who, when we don’t understand something like how to grout tile or make banana bread, we Google it, Cindy and I retreated to the computer and looked up cerebellar atrophy.

There is nothing like that first Google search for your degenerative brain condition. The 18 seconds it took the internet to produce 1.2 million results were agonizing. Amazingly, it only took about five seconds of scanning the results to scare the poop shit out of me. When I read the words irreversible, and paralysis, and death out loud, Cindy gripped my hand and said, “Let’s see the doctor before you start diagnosing yourself.”

I closed the laptop and hugged her, and we cried together. Nicholas Sparks style.

Later that night, after the kids were asleep, Cindy and I had one of those adult conversations regarding the news of the day. We decided she’d take the kids to school the next morning and go to work and my mom would accompany me to the appointment with Dr. Simon.

It’s amazing how the spectrum of your life can change so drastically in a matter of hours. One minute you’re watching Danny laugh at poop, and the next you’re on the couch with your wife, tracing her nervous knuckles with your thumb, talking quietly about your degenerative brain condition.

And that’s the thing. If the news of the day had been Danny’s poop fixation, Cindy would have listened. We’ve been together since we were 16. In that time she has listened to me tell hundreds of stories – some funny, some sad. Trite stories about work. Booze-fueled degenerate stories that only the four people involved find funny. Stories that aren’t really stories, more like Seinfeldian musings on life. But she listened. Always.

Cindy had taught me the power of listening. How the deliberate act of listening has nothing to do with the topic and everything to do with honoring the relationship. Look, I’m no Dr. Phil, but I’ve come to believe that listening, truly listening, to someone is the greatest compliment you can give them. It’s like saying, “Hey, we’re both tragic creatures, but for this nugget of time I’m going to put away my tragedy to focus on yours.”

I believe we all want to be heard. And if you can find a spouse, friends, colleagues, and doctors who will listen to you, I implore you to hold them close because sooner or later we all need someone to talk to.

Dr. Paul Simon’s office was tucked in a nondescript complex I had spent most of my life driving by. Mom and I entered the office and stepped into 1976: cherry wood paneled walls and an orangey matted carpet. Framed waterfall pictures and horse paintings were tacked randomly in the waiting room. A receptionist sat with the back of her head to us in what resembled a penalty box. She looked like a receptionist plucked from a ’70s high school yearbook. High gray hair, purple turtleneck, big and tinted reading glasses. She clanged away on a typewriter even though there was a perfectly good computer on her desk. It wouldn’t have surprised me if Doc Brown and Marty McFly were in the waiting room discussing Flux Capacitors. Beyond the penalty box was another little room stacked floor to ceiling with manila file folders. Old-school files before hard drives and flash drives and computers.

The receptionist took my name and my 15-dollar co-pay and told us to have a seat. The waiting room was empty and seemed like it may have been empty for a long time. The pleather chairs looked like yard sale leftovers, and the coffee table could have been the one your grandmother had in her living room. Good Day Philadelphia aired on a tube TV. A segment on fall fashion trends for men informed me that red capris were in and khaki-colored khakis were so last year, which made sense because I was wearing khaki-colored khakis. Everything in the office, even my pants, was from another time.

Mom sat with the back of her head pressed against the panel wall. Her eyes were closed. She looked tired, and I had a feeling these last few hours had been tougher on her than on me.

A nurse entered the waiting room and called my name. She wore pink modern scrubs, and a rose tattoo was inked on her right forearm. She looked out of place. Like she had wandered into Mike Brady’s living room. She smiled and told us to follow her, and I felt a little more at ease. She led us down a hallway into the biggest examination room I’ve ever been in. Aside from the obligatory examination table, there were two chairs, another coffee table, a changing closet, and a fish tank with a Fat Nemo clownfish floating inside. There was a Hi-Fi record player with wooden speakers that shared a shelf with gift shop knickknacks: a mug announcing “Virginia is for Lovers,” a miniature Statue of Liberty, a snow globe with the Golden Gate Bridge inside, and a glass ashtray from St. Louis. And in a way, the weird, the tacky Americana decor magnified the absurdity of the last 24 hours of my life.

Dr. Paul Simon hurried into the room studying the printouts of my MRI. He stopped and stood in the middle of the room with his eyes glued to the MRI as Mom, Fat Nemo, and I waited. When he looked up, Dr. Simon bore an uncanny resemblance to his famous namesake in a lab coat. Of course, he is not that Paul Simon. But in moments of crushing heartbreak, everything felt distorted. It was difficult to tell where fantasies ended and reality began.

“Jason Armstrong?”

“Hello.”

“Can I call you Jay?”

“ ‘You Can Call Me Al.’ ”

Dr. Simon didn’t laugh.

If you didn’t laugh, I suggest you familiarize yourself with Paul Simon’s songs right now. I’ll wait. I always play music for my children. My father played music for me. In troubled times, I’ve found great refuge in the comfort of song. As I tell you the rest of this story, I’ll make allusions to Paul Simon songs. My hope is that when you finish reading, you’ll retreat to your music and discover comfort in some Paul Simon songs too. My personal favorites are woven into the rest of this story. See if you can find them.

He continued to study the MRI. Except for the bubbles from Fat Nemo’s fish tank, there was only “The Sound of Silence.” Finally, he said, “Jason, when did these symptoms start?”

I told him about my dizziness and leg weakness that began a few weeks before. He listened, standing with his arms folded, occasionally scribbling on a yellow notepad. His demeanor was professional and reserved until I told him that, after I spoke to Dr. Thomas yesterday, I’d been doing some research on my own.

He looked up. “So, you’re playing doctor?”

I sense I’m standing on a “Bridge Over Troubled Water.”

“No. Just curious.”

“Okay, so what do you think you have?

“Excuse me?”

“From your Googling, what do you think you have? I’ll tell you if you have it or not.”

I’m suddenly thrown into a game of diagnosis roulette. I looked at Mom. I looked at Fat Nemo.

“ALS?”

“No.”

“Huntington’s disease?”

“No.”

“Cancer?”

“No.”

“Doctor, this is not a fun game.”

“I understand. Do you want to know what I think you have?”

Sheepishly, I answered, “Yes.”

He explained my MRI clearly revealed a diffuse cerebellar atrophy. However, it was his opinion that atrophy can indicate the onset of Parkinson’s or a form of spinocerebellar ataxia, SCA for short.

Thanks to Marty McFly, I knew about Parkinson’s. SCA sounded scary, and I didn’t ask. But Mom did. Moms are good for that. Asking the hard questions their children would rather avoid.

“There are many different strands of SCA. And we can’t know which strand Jason has until he has more testing. Some strands progress slowly over years, and others progress quickly and are fatal.”

I looked at Mom. Then at Fat Nemo. Neither said a word.

Dr. Simon wrote a few scripts for me and urged me to get tests and blood work done immediately. He also said he wanted me to go see Dr. Reardon, a renowned neurologist at Jefferson Hospital in Philadelphia.

Mom and I left the office in silence, and as we crossed the parking lot, she slipped her arm through mine and rested her head on my shoulder. If I was a dead man walking, Mom just wanted to be as close to me as life allowed. Mom had always been that way. Trying to take away her son’s pain. So much of what I have written in this book is my attempt to feel what Mom has felt. To recognize the deep, uncompromising love that welds the bond between parent and child. “A Mother and Child Reunion.”

We got into the car, and Mom drove toward the testing center while I Googled spinocerebellar ataxia on my phone.

“Homeward Bound.” I wish I was.

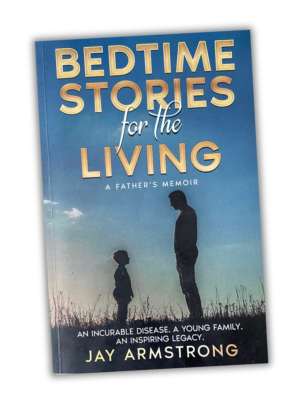

BUY YOUR COPY TODAY!!

This blog post is a chapter preview from the book Bedtime Stories for the Living.