In the more than 60 years I’ve known the Hunt family, I have three rings from the first three Super Bowl titles the Chiefs won. To my complete surprise, they presented the third one to me in October of 2023. I also was invited to the Super Bowl pregame festivities. Pretty amazing because I hadn’t worked for the Chiefs for 35 years.

On June 4, 2023, I saw Lamar Hunt Jr. at the George P. Toma Wiffle Ball Field at the Hollow. He had brought senior citizens and schoolchildren for the day to watch and play wiffle ball.

I asked how his mother, Norma, was doing.

“Oh, she’s great,” Lamar Hunt Jr. said. “Thanks for asking.”

A few hours later, I went home, turned on the television and saw Norma Hunt had passed away. What a wonderful woman.

When the Kansas City Chiefs opened their 2023 season, they wore NKH patches on their jerseys to honor her.

Norma Hunt is part of Super Bowl history. She married Lamar Hunt, the Kansas Chiefs’ original owner; she played a role in the naming of the NFL championship game; and she attended the first 57 Super Bowls. After neither of us attended Super Bowl LVIII in 2024, there aren’t many left who have been to every game.

You can just about count them on one hand now.

I remember the first Super Bowl as well as the 57th.

In the days leading up to the Chiefs’ Super Bowl I contest against the Green Bay Packers, Mr. Hunt asked me to drive with him to pick up Norma at the airport. I took a quick shower, then joined him in the lobby of the Sheraton.

When we went to the parking lot, the car was gone. Coach Hank Stram took it, something he did all the time.

After trying to find someone with a car, we finally rented one for a few hours from a man who worked in the Sheraton’s kitchen.

The beat-up station wagon we rented was on its last wheels. To make matters worse, we got lost and ended up in Watts. The beat-up car may have been a blessing in disguise there. Just 17 months earlier, riots took place in the Watts neighborhood and the surrounding areas of Los Angeles in August 1965.

Finally, we made it to the airport. When Norma saw us, she sat down and started laughing. She never lost the common touch. Neither did her husband, who listed his phone number in the Kansas City phone book.

Superball

I remember Norma regularly sitting with the rowdy Wolfpack in the bleachers.

In 1966, she bought her children Zectron Superballs, introduced by Wham-O. They were considered the bounciest balls ever made.

When Lamar Hunt saw his children playing with the balls, he started thinking, “Superball, Super Bowl.”

However, he wasn’t convinced that this should be the name of the NFL’s championship game. Neither was NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle. Even fellow NFL owners chuckled when hearing it.

“If possible, I believe we should ‘coin a phrase’ for the Championship Game,” Hunt wrote, according to Michael MacCambridge’s book America’s Game. “I have kiddingly called it the ‘Super Bowl,’ which obviously can be improved upon.”

Rozelle and Hunt settled on the “AFL-NFL Championship Game” for the first couple of years.

Manicuring the field for the first title game in Los Angeles was a pretty normal procedure. I arrived five days early and worked with a small screw of men and a man named Bob Williams. They were all hard workers.

They had this sprayer they took everywhere. I had a 3-foot-by-4-foot trunk with all the equipment I needed. I still have that trunk in my basement.

We cut the field, swept it, groomed it, watered it with Hudson metal garden sprayers and painted the lines and the logos.

Today, we start field preparations weeks in advance. About 30 men and two 45-foot tractor trailers full of equipment are involved.

For the first 27 Super Bowls, we spent between $500 and $1,000.

Now, I believe the cost had increased to an estimated $700,000 to $800,000 for the field and maintenance.

Has it been better? I’ll hold off on my opinion on that for now.

For the first championship game, some media originally named it “The World Series of Football.” However, others followed Mr. Hunt’s lead and called it the Super Bowl. If you watch NFL Films in its 30-minute highlight montage of the first title game, producers called it Super Bowl I.

Finally, by Super Bowl III, the name stuck.

Some wondered what kind of future the Super Bowl had when the first game had about 30,000 empty seats. However, we later found out that more than 65 million people had watched the game. Both CBS and NBC televised it. I thought the younger generation would be interested in the game.

The Orange Bowl in Miami played host to the next two Super Bowls.

When we arrived for Super Bowl II, the Green Bay Packers vs. the Oakland Raiders, the field was in bad shape. At that time, the NFL had a runner-up game the week before the Super Bowl, and that year it was played in the rain.

When we arrived on Monday, there was a clarinet embedded near the center of the field.

Because we only had a week, Dr. James Watson and I came up with a recipe to get the grass to grow quicker.

It’s called pre-germination. We took 100 pounds of rye grass seeds and placed them in 55-gallon drums.

On Day 1, the seeds were soaked for eight hours in water containing Bov-A-Mura – liquid cow manure – and Aqua-Zorb, a wetting agent. This solution is removed and the barrels are refilled with fresh water every eight hours.

Within four days, the seeds sprouted. We then mixed it with equal amounts of Milorganite fertilizer or calcined clay in a cement mixer. Calcined clay really soaks up the water.

As NFL special events director Jim Steeg will attest, it’s a smell you just don’t forget unless you drive past Midwest farms in the middle of the summer.

During this process, we paid more attention to the temperature of the seed in the barrel and how long it sat in the water. The seeds needed air and moisture and had to stay within a certain temperature range.

After aerifying the field lightly, we applied the seeds to the soil with pin spikers.

By Friday, we could cut the grass, and Saturday we could paint it. Gametime was Sunday.

It’s the same process we used until Super Bowl XXVII in 1993.

Sometimes, there’s only so much you can do.

Super Bowl IV in 1970 had a bare field in New Orleans. The end zone had hardly any grass. During the week, the weather was freezing. There was a big storm the night before the game, and the restrooms froze.

What I did during the week was put down wood chips, scatter sawdust and paint the field green. There were wet spots, but the players didn’t complain because they still had good footing.

I remember Otis Taylor running by me after catching a 46-yard pass from Len Dawson to seal the Chiefs’ 23-7 victory over the Minnesota Vikings.

For two years in a row, AFL teams had won against their NFL foes, and the merger between the leagues showed the title game wouldn’t be as one-sided as some thought. In fact, after Green Bay’s first two Super Bowl wins, the AFL/AFC teams would win eight of the next nine contests.

Little did we know it would be 50 years before Kansas City would return to the Big Game.

But I kept returning year after year.

This letter from the commissioner shows what the NFL thought of my work:

PETE ROZELLE

410 Park Avenue

New York

Feb. 6, 1978

Dear George,

The enclosed column from a Tampa area paper pleased me greatly because I like you to know that your work is noticed and greatly appreciated by others in the league office.

But, of course, we must be your #1 fans! The Super Bowl was just magnificent and I heard so many compliments about it from those at the game, I only wish you could have heard them, too. And certainly, no Pro Bowl field ever looked better.

Thank you for always giving something extra and achieving an outstanding result whether under controlled conditions of a domed stadium or while contending with adverse weather conditions outside.

Incidentally, this is my version of a handwritten letter – a throwback to my old days as a P.R. man.

Best wishes always.

Regards,

Pete

BUY YOUR COPY TODAY!!

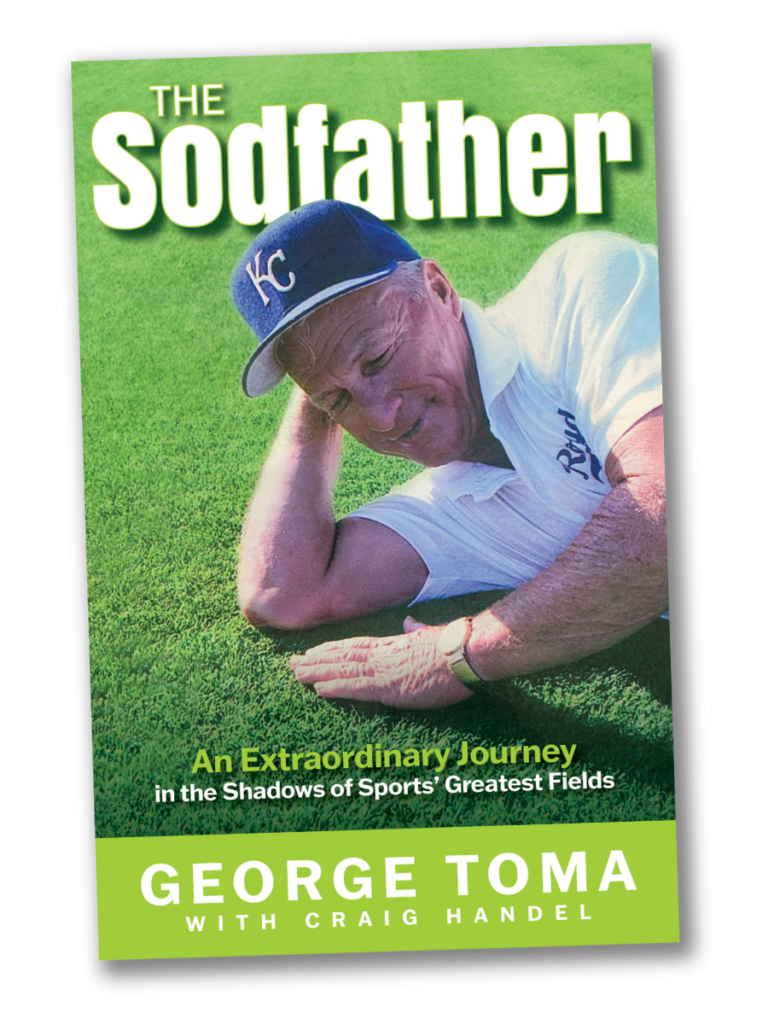

This blog post is a chapter excerpt from the book The Sodfather.